By Kendall Custer

On March 19th, 2003, residents of the Denver Metropolitan area and the adjacent foothills awoke to a winter wonderland. However, instead of thoughts of stressful work commutes and plans for backyard snowball fights, a sense of cabin fever was settling in. This was the third day of one of the largest snowstorms in Denver’s history. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Regional Climate Center snowfall accumulation database, some residents saw up to thirty inches of snow over four days. As a result, thousands of residents were on lockdown without power and unable to leave their homes.

While the March 2003 blizzard was one of the more memorable snowstorms in the past fifty years, Coloradans are familiar with large blizzards and their inevitable consequences. Other notable Denver storms include the Christmas 1982 blizzard that dropped nearly twenty-four inches of snow, and, more recently, the March 2021 “Pi Day” blizzard that buried the Front Range in twenty-seven inches of snow (data courtesy of the Denver/Boulder National Weather Service [NWS] Weather Forecast Office [WFO]). Large snowstorms like these often result in significant road and travel closures, power outages, and property damage, which are difficult to prepare for and a consequence of inaccurate weather forecasting. Yet, despite what many Coloradans believe, the local meteorologists are not at fault. It is the unfortunate reality of living near large mountain ranges, such as the Rocky Mountains, where radar and satellites struggle to track current weather patterns accurately and topography can change conditions on a dime.

Growing up as a Colorado native who has heard the stories of (and even lived through) these intense blizzards, I developed a passion for mountain meteorology and often wonder: how do we improve weather forecasting for the mountainous terrains that make up our colorful state? What can we as meteorologists do to gather accurate information to help major metropolitan areas mitigate impacts? These questions inspired me to choose the topic of my senior capstone project: investigating the patterns associated with mid-latitude cyclones and how they impact snowfall over Metro Denver and the Foothills.

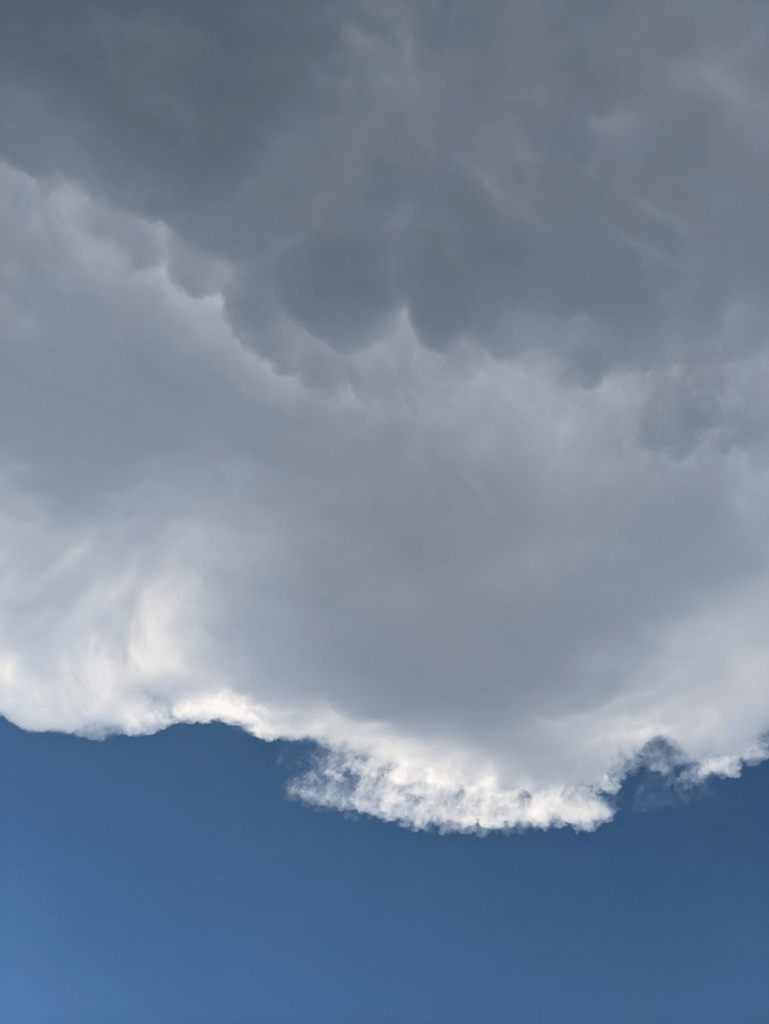

As defined by NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), a mid-latitude cyclone is a low-pressure system that forms between 30° and 60° latitude, including most of the continental United States, excluding the Gulf Coast and Florida. These pressure systems fall on the “synoptic-scale” (NOAA), meaning their size can range from 620 to 1,500 miles, i.e., the size of one state to multiple at once. If you’ve ever looked at a weather map on the news before, you’ve likely seen a mid-latitude cyclone’s familiar “T-Bone” structure (Schultz & Mass). It consists of a red “L” (for the center of the low-pressure zone), a red line with semi-circles (a warm front), followed by a blue line with triangles (a cold front), and occasionally a purple line with alternating semi-circles and triangles (an occluded front). When looking through the lens of thermodynamics and atmospheric physics, a more complex framework appears, including what is referred to as “conveyor belts”: air bands that vary in temperature, moisture, and density (Lackmann). In a mid-latitude situated over the Midwestern United States, air flows counterclockwise around the low-pressure system. As it does so, warm, moist air is pulled from the Gulf, creating the “warm conveyor belt.” Meanwhile, an east-to-west “cold conveyor belt” of cold, moist air forms ahead of the warm front. When these two belts meet, the warm conveyor belt is quickly forced upward, where the air cools and condenses into clouds before falling as precipitation.

In my research, I hypothesize that when a mid-latitude cyclone brings blizzard conditions to Denver, the system’s low-pressure center is most likely positioned over southeastern Colorado. Here, the warm and cold conveyor belts have an easterly flow when they reach the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains and encounter upslope forcing, a process where topography redirects wind from horizontal to vertical flow. During this, the air is rapidly cooled, condensing into clouds and producing significant snowfall over Denver and the Foothills.

As mentioned earlier, forecasting these large, heavy snowfall events is challenging in regions like Denver, which is why research like mine focusing on the patterns of meteorological processes is essential. Improving the accuracy and timeliness of numerical weather forecasting can prepare residents (i.e., supply stocking), allow government agencies like the Colorado Department of Transportation to prepare roads by dropping sand/magnesium-chloride to prevent icing, and provide time for energy companies such as Excel to plan for power outages. In the end, these preparations not only keep metropolitan areas like Denver operating during large snowstorms but can save Coloradans’ lives, enforcing the necessity of improved weather forecasting and mountain meteorology research.

References

Denver/Boulder Weather Forecasting Office. (n.d.). Denver’s Fall/Winter/Spring Statistics. National Weather Service. https://www.weather.gov/bou/DenverFallWinterStatistics.

Lackmann, G. (2011). Midlatitude Synoptic Meteorology: Dynamics, Analysis, and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society.

NESDIS. (2018, June 22). Mid-Latitude Cyclone on the First Day of Summer. NOAA. https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news/mid-latitude-cyclone-the-first-day-of-summer.

NOAA Satellites. (2019). Powerful Storm System Seen by GOES West [Photograph]. NOAA. https://www.flickr.com/photos/125201706@N06/47380253391.

Schultz, D. M., & Mass, C. F. (1993). The Occlusion Process in a Midlatitude Cyclone over Land. Monthly Weather Review, 121(4), 918-940. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121%3C0918:TOPIAM%3E2.0.CO;2.

Synoptic Meteorology. (2023, May 16). NOAA. https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/synoptic.

I am a Senior Atmospheric and Environmental Science Major with a Meteorology Specialization and a minor in Mathematics. The question of when I first became interested in the weather is greatly debated in my household, ranging from me searching our yard every day for fallen weather balloons after a local TV meteorologist visited my elementary school to when I would beg my dad to pull over so I could take a photo of a cool cloud. Regardless, every childhood fascination with something weather-related led me to today, where I have developed a passion for synoptic-scale meteorology, cyclogenesis, mountain meteorology, severe weather, and investigating the unknown. After graduation, I plan to continue my education by earning my master’s degree, ideally internationally (fingers crossed!), and eventually working in my dream career as an atmospheric researcher. When my head is not in the clouds or my textbooks, I enjoy a range of hobbies, including creative writing, arts/crafts, paddleboarding/hiking with my dog Hershey, and powerlifting.