By Christy Tidwell

“[Zines] are practices of ‘poetic world-making’—poetic not in the sense of a poem on the page (although they can be this too),

but in the sense of poesis: the process of creating something that did not exist before.”

– Gwen Allen

The classes I teach create communities. Students get to know each other as they learn the course material, and they share ideas and work with each other. This is a form of world-making, even if temporary, and I love this about my classes. But I don’t want the connections and sharing to stop at the classroom door or to be forgotten when the semester ends. The goal is for my students to connect what they’re learning in class with the rest of the world, to share what they’ve learned with others, to hear what others have learned, and to join and build other communities.

Finding ways to do this can be challenging, but it’s not impossible.

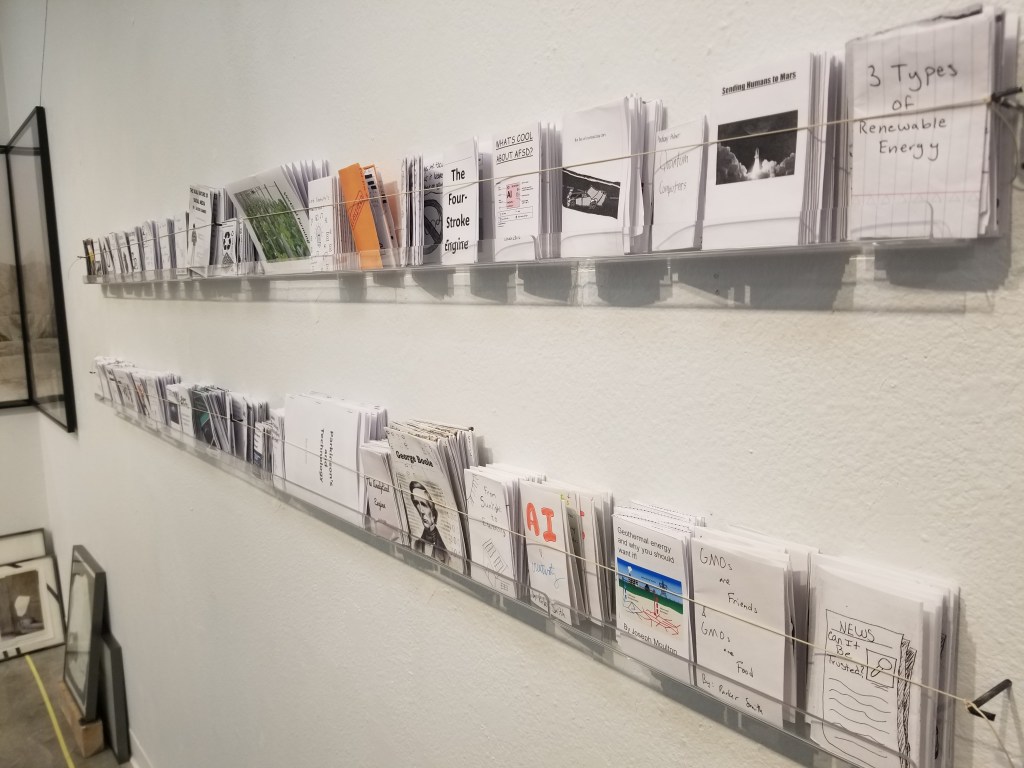

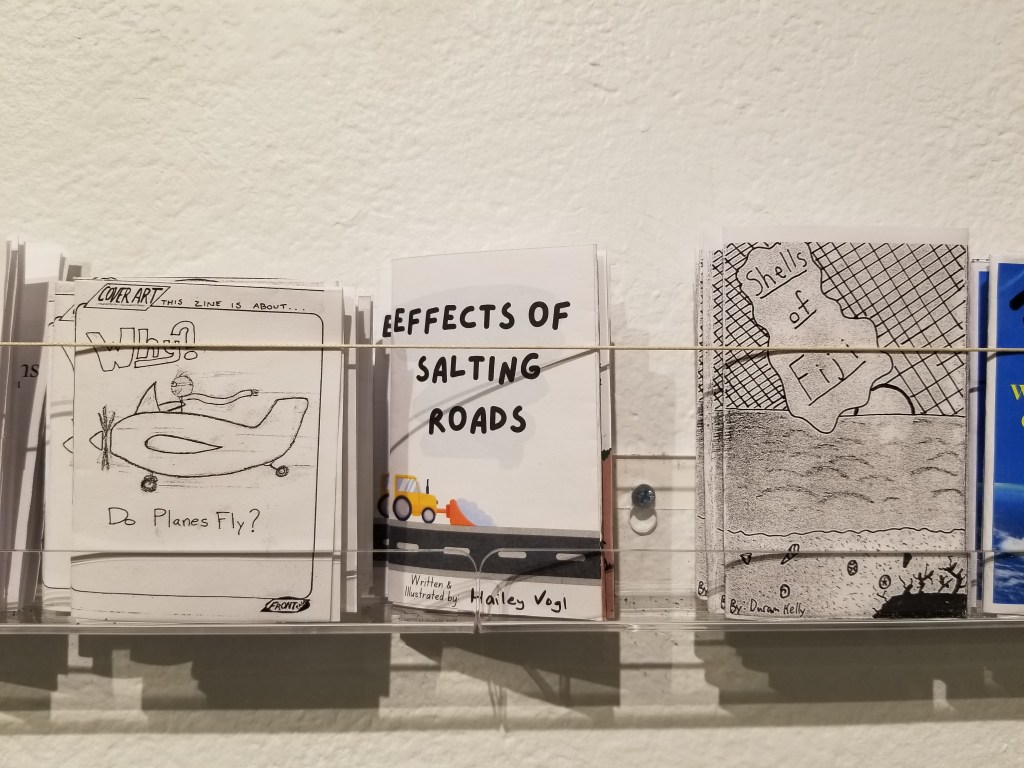

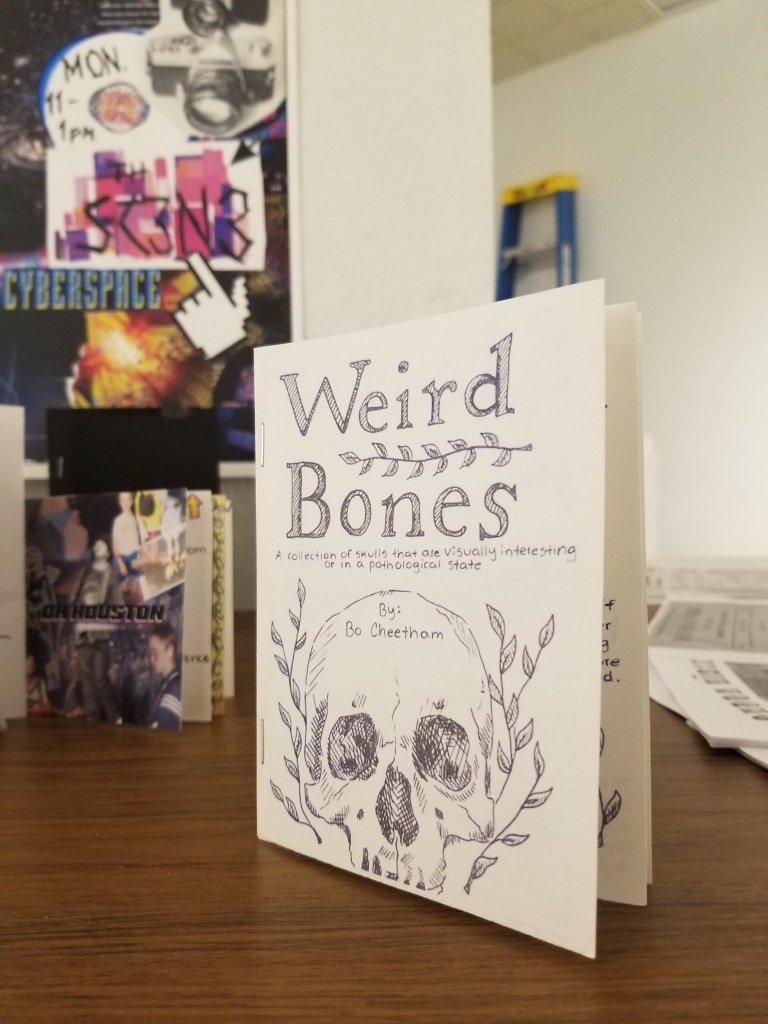

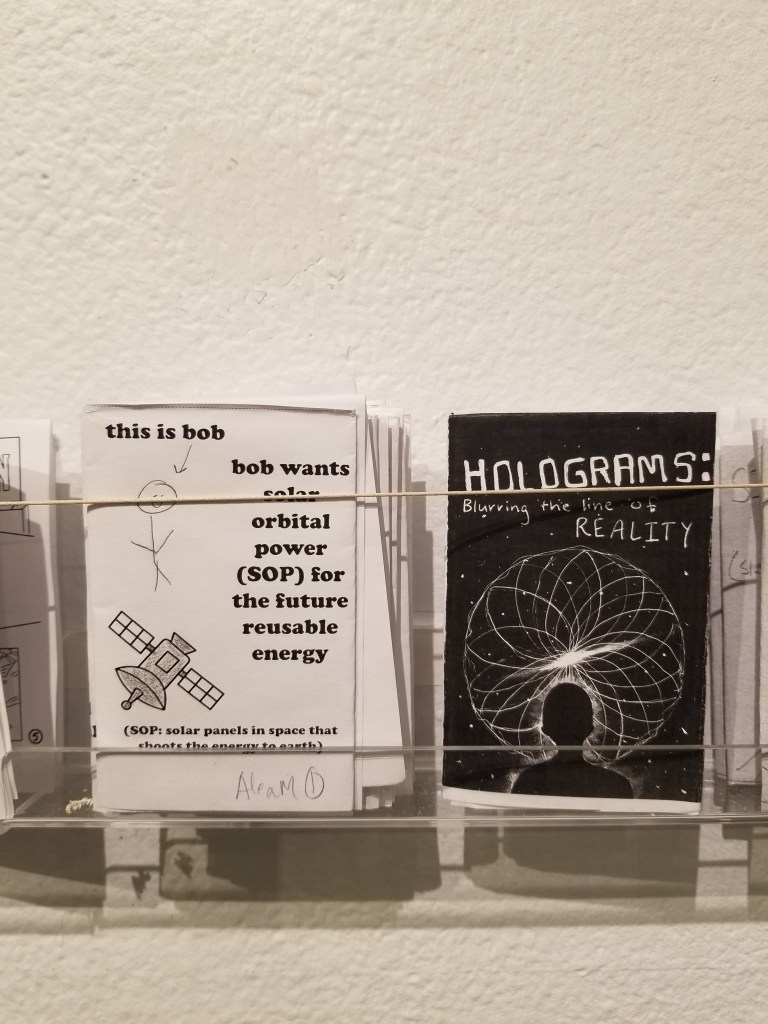

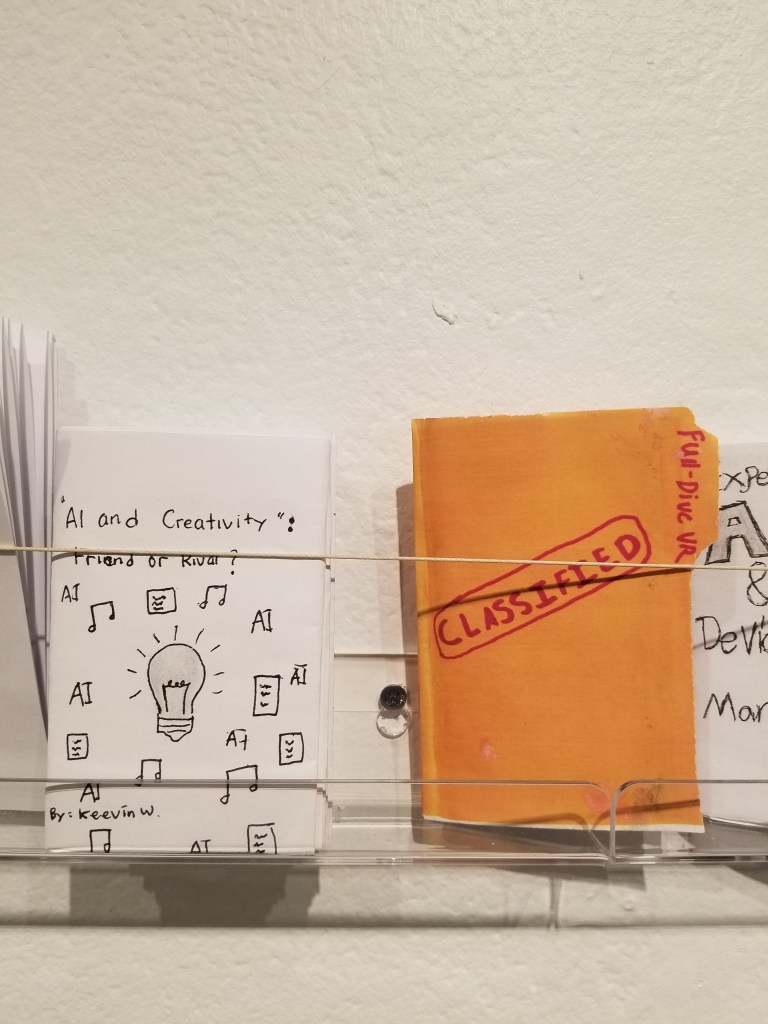

This semester, as a way for students to connect across classes and share work with broader audiences, a few of us in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences department (myself, Matt Whitehead, Evan Thomas, Erica Haugtvedt, and Mary Witlacil) put on a series of zinemaking events that culminated in a Zinefest in the Apex Gallery on December 4th. Zinefest was an all-day come-and-go event that displayed the zines students made in classes (and, in a few cases, just for fun!), provided some examples of interesting zines made by others, and gave visitors a chance to make their own zines. (If you missed it this year, watch out for another event next year!)

This event let students share some of what they have learned this semester, giving them a broader audience, and it also connected them to students in other classes and to the audiences who came to Zinefest. While I did not count the number of visitors during Zinefest, the gallery filled several times and was rarely empty. Some people walked through relatively quickly and took in only a few zines; others stayed for quite a while, standing and reading multiple zines before finally deciding on some they wanted to keep. One student – who will remain nameless for obvious reasons – wrote in a reflection afterward, “I spent almost 2 hours there and accidentally missed class, so I would say I had a good time.” Although I would (of course) never encourage a student to miss class, this indicates that Zinefest offered this student something meaningful.

Because most students were asked to bring multiple copies of their zines, visitors could take a copy of one if they were particularly interested in its ideas or really loved it. Hopefully, they will re-read any zines they took, remember the event, and maybe even be inspired to make their own! Leaving with a material artifact helps the experience and community created through this event extend past Zinefest itself.

As an event, Zinefest promoted connections and community; as a practice, making zines (even without an event like Zinefest) provides us all with an opportunity to create something new – to engage in world-making – and to share that something with others, without requiring elaborate technology or infrastructure, refined skills, or many resources. Anyone can make a zine, and that’s what’s so beautiful about them.

But What Are Zines?

When introducing these events and activities this semester, I found that many people weren’t familiar with zines (pronounced zeens, as in the last syllable of magazine). Zines may not already be familiar, but they are easy to get to know.

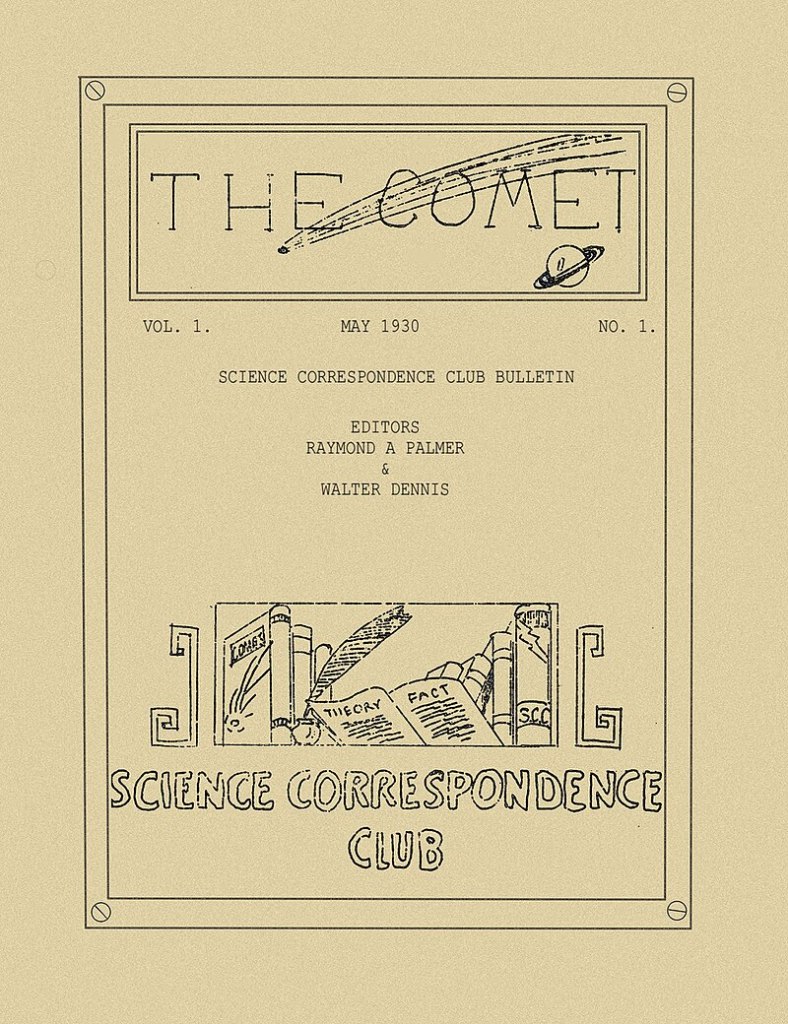

Zines are a kind of DIY publishing, often low-budget and informal, but varying tremendously in style, methods, skill level, and content. Historically, they have been used by groups who either cannot publish in traditional venues or who do not want to. For instance, one of the earliest modern examples of a zine is a science fiction fanzine called The Comet, which dates from the 1930s. Science fiction fans could – and did – write letters to magazines that published science fiction, but creating their own publication gave them more space to develop their ideas and community.

Another early 20th century example – Vice Versa, often described as the first lesbian magazine – highlights the way that a zine, shared through informal networks and outside of official avenues, can give a marginalized group the chance to connect with each other quietly, without drawing unwanted or harmful attention to themselves.

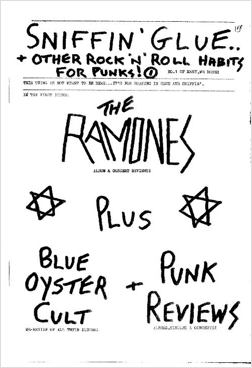

In the 1970s and 1980s, zines also became associated with punk subcultures (you can find lots of examples of punk zines collected here). Sniffin’ Glue is one early and influential example of this, publishing monthly issues about punk music and culture because it wasn’t being covered elsewhere but also because its DIY ethos didn’t always fit in glossier music magazines. This influence continues throughout the late 20th century and to the present, appearing in the 1990s riot grrrl scene, for instance, as part of queer communities, and as a form adopted by various artists.

Today, fans, marginalized communities, and subcultures don’t need to make physical zines and share them through the mail. They can use the internet – and they often do. But many people still make zines anyway, both in hard copy and digital.

The Small Science Collective is one example of contemporary zinemaking that expands the potential of zines. They share zines on topics like tardigrades, spirals, and ocean acidification rather than science fiction, punk music, or personal experience and identity. These science zines are still small and DIY, but they emphasize sharing scientific ideas in an accessible and appealing way. (These zines are the model for the work I asked students to do in STEM communication and science-oriented classes, more than the fanzine and subculture zines are.)

And many other artists are still drawn to the zine format. Try searching for zines on Etsy, for instance, and you’ll find an abundance of creators making and selling their zines. Or check out itch.io, which is a platform mostly for gamers but which also has lots of zinemakers sharing their work and is easily searchable. Zines also pop up regularly at indie bookshops and festivals (I’ve collected quite a few from Quimby’s in Chicago).

Why continue to make zines when the internet exists? Fundamentally, for many people, it’s about the material object and the way that something meaningful is shared with the physical thing itself. When you make something with your own hands that you can give to someone else, you make more than the object. You make a connection.

Zinemakers often emphasize this connection. For instance, Scott Treleaven writes, “Zines proliferate where the lines of communication become specialized, tenuous, and dangerous. . . . As anyone who loves them will know, to hold that handmade object in your hand is to have another’s hand clasped in yours. They say: if you are reading this, I am not alone and you are not alone.” This may be especially true for groups and topics that are outside of the mainstream, but there’s something inherent to the form, too. As Julia Bryan-Wilson says, “For me, a zine is not just any little newsletter, but a specific form of self-publishing that is at the same time a method of community formation.”

“They say: if you are reading this, I am not alone and you are not alone.”

Making and sharing zines itself brings people together, even for a class project and even without the marginalization that has often accompanied zines throughout history, and many of this semester’s students felt this connection. Students in one class commented, for instance, on how Zinefest had “the overall vibe of people going around and supporting others’ work when they might not even know the author” and it felt “like a community project” when a group came in together.

Why Use Zines in Class?

Creating this kind of community is one reason to have students make and share zines, but zines themselves might still seem somewhat un-academic, un-scholarly, or un-professional. Fair enough! Zines are not academic, scholarly, or professional. That is, as discussed above, part of their appeal.

There are multiple ways in which they can be related to course goals, however, not only in art classes like Drawing or Design but also in classes focused on communication (e.g., composition or STEM communication) or in classes focused on specific content (e.g., Introduction to STS, Humanities & Technology, or Computers in Society).

One key element of zines is that they are often smaller, shorter publications. The zines we asked students to make and that we provided as examples this semester tended to be focused on just one idea, often in minizine format (using an 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper folded into 8 pages). This smaller scope makes zines an ideal form for thinking about how to communicate an idea quickly. If you only have 8 very small pages, how do you tell a story, inform about a topic, engage the reader, and make it look good? It’s a challenge!

This is exactly the kind of challenge that arises in other formats and contexts, too, however, when students need to communicate complex STEM topics to wider audiences and to do so quickly. Sometimes they may have a whole 30-minute presentation period to develop their points; sometimes they may have the space of a full policy paper to delve into the details; many times, however, they will have something more like a minute or two of talking time or a paragraph of writing space. The formatting will vary, but if they can explain why, for instance, salting the roads is a meaningful issue in a minizine, then they can also do so in other contexts.

As Dr. Evan Thomas explains, his students in composition and STEM communication classes were asked to make zines as a way to practice craft, stance (or voice), and risk – all key elements of writing and communication, no matter the form. By practicing these things in zine creation, students are asked to go beyond a typical and familiar writing format like the college essay and consider how communication might change in different contexts and into the future. Writing and communication are not static; they grow out of communities. As the communities we belong to change, so do our forms of communication and, Thomas says, “zines represent the kind of thing that STEM fields might need to experiment with in order to keep the conversation moving forward.”

Going Low-Tech at a STEM School

Moving forward, however, is often imagined as being very high-tech. We envision futures of shiny robots, sleek jets, and more and more automation. And Mines students – as students at a STEM school who are working toward designing and engineering elements of the future – can be particularly susceptible to this way of thinking.

But progress doesn’t have to mean high-tech – at least not only that – and zines are a good reminder of the value of low-tech skills. You can make a zine with your computer, and some students opted to do this, but to share the zine at an event like Zinefest still requires manipulating the hard copy – folding, cutting, stapling or binding. This was actually the biggest challenge my students reported in making their zines, a reminder that the computer cannot do everything for us. More importantly, in reflections on their zines, many students who made their zines digitally reported that they wished they had made theirs by hand because they appreciated the handmade ones so much. They experienced them differently, as more meaningful, inviting, authentic.

The students who opted not to make theirs by hand often made that choice because they thought they wouldn’t be able to draw well enough, but zines have room for messiness and for a wide range of technical abilities. Some of the zines that students ultimately reported liking the most were those that showed the creator’s personality and the work they put into it but that were not necessarily especially refined. That combination makes for a zine that is completely unique and individual.

In 1976, Adrian Piper asked, “Suppose art was as accessible to everyone as comic books? as cheap and as available?” Zines are a perfect medium for making art this accessible – or even more accessible. Anyone can make a zine. Anyone can share their zine. It doesn’t have to be perfect to be worth making or sharing.

The question of computer-created rather than handmade zines can be placed in historical context, too. Zines were made possible by technological advances like printing presses (in precursors to modern zines), mimeograph machines, and photocopiers. These advances automated the process of reproduction to make it easier to copy and share what people create. In that sense, zines are still representative of high-tech progress, and adopting new technologies to make and share zines is in line with that history. But the new technologies that made zines possible helped to share what a person made by hand, not to make the zine itself.

This combination of high-tech (methods of reproduction) and low-tech (methods of creation) is important to zines, and recognizing this relationship is crucial to gaining a better understanding of our human relationship to technology and progress.

This is, in turn, at the heart of STS as a field and a degree here at Mines. How do science, technology, and society relate to one another? How do people actually use technology? What are the ethics and impacts of using technology in specific ways? These are key STS questions, and they are built in to the zinemaking process, whether zinemakers always think about it or not. Making zines is, as seen above, a sequence of choices about not only content but practice – what technologies will you use to create your zine, and for what purpose?

Making zines and, in doing so, considering where we rely on technology and where we do not provides a way to think about what parts of communication, creation, and community-building we want to remain human. If, as the quote I opened with states, zines are processes of world-making, it’s worth remembering that world-making is a series of choices about what kind of world we want to live in. Anyone can make a zine. Anyone can imagine a future world. Together, in communities, we can create the future.

References & Credits

All quotes not from students or faculty here at Mines are from essays in Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, a book edited by Branden W. Joseph and Drew Sawyer that was created to accompany a zine exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. All Zinefest photos and video taken by me.

Thanks to Matt Whitehead for his significant work on running zinemaking events with me and setting up the Apex Gallery for Zinefest, as well as for loaning me Copy Machine Manifestos. Thanks to Evan Thomas, Erica Haugtvedt, and Mary Witlacil for supporting these events throughout the process (brainstorming, bringing additional materials, getting students involved, etc.). Thanks to Arana Peters and Kyle Knight for logistical and departmental support. Thanks to all the other faculty who brought students to events and encouraged them to get involved. And, most of all, thanks to the students who created zines! There were between 175 and 200 zines at Zinefest, the result of many students’ work and creativity, and obviously this would not have worked without them.