By John Dreyer

When I was in my early teens I bought Mr. Scott’s Guide to the Enterprise. This book was just a technical manual for Star Trek and, as a young fan, I was pretty happy. One aspect the authors addressed was eating on board a future starship using a replicator. Essentially a 3D food printer, the replicator could make anything you desired. The author even included a menu of choice dishes. This book is only one place where food in science fiction is addressed. From the cornbread in Aliens to the generic-looking dinner in 2001: A Space Odyssey that David Bowmen grabs while it’s still too hot, food has had a place in storytelling.

But what about real space exploration? Do astronauts get Yankee Pot Roast? Space food has had a long developmental arc, often supplemented by industry, that seeks to put nutritious and tasty food at the fingertips of astronauts and, later, consumers.

The first food in space was carried by Yuri Gagarin. His meal was two tubes of pureed meat and a tube of chocolate sauce. For the designers of the meal, there was a question if he could actually eat and digest in zero gravity. In his first American orbital flight, John Glenn consumed a tube of applesauce, which he claimed to have enjoyed. Tube foods are not exactly appetizing, and nutrition in space was still in its infancy. There were also questions of taste and texture. As NASA began to work towards Apollo and the moon landing, it was realized that better food was necessary.

There were many technical issues to consider when sending food to space. For instance, all food would need to be processed in some way as there would be no refrigeration aboard. Another aspect was to produce foods that negated all crumbs. Crumbs in zero gravity would get into everything and possibly cause issues with controls. For example, toast in space. NASA developed toast cubes, which were similar in texture and shape to croutons. This was a good idea but one that did not resonate with the astronaut corps. John Young on Gemini 3 brought up a corned beef sandwich from Wolfie’s sandwich shop near pad 19 at the Cape for his commander, Gus Grissom, to enjoy. While Grissom appreciated the joke, he was worried about crumbs clogging the instruments. The sandwich was quickly put back in Young’s pocket. Amazingly, this resulted in a Congressional hearing and tighter controls on what could be brought into space. Sandwich cubes were supposed to solve the crumb problem. So, NASA developed small bite-sized cubes that were freeze-dried and coated in gelatin. Pop one out of the package, rehydrate in your mouth for a delicious culinary experience. Unfortunately, the idea was much better than the execution: they tasted awful.

As the Apollo project chugged along, the food began to get better. Bacon cubes, shrimp cocktail, and ice cream were among the foods developed for the multi-day moon landing missions. Buzz Aldrin was even able to perform communion on the moon with a tiny amount of wine and wafers. Astronauts were also able to celebrate a traditional American Thanksgiving dinner packaged in rehydratable pouches, freeze dried cubes and cans. Shrimp cocktail proved the most popular throughout NASA’s history. Easy to rehydrate and still taste good, it proved a winner for the crews.

Even though the food got better, it was still bland by design. The meals provided to the Gemini and Apollo astronauts were usually made with as little spice as possible to avoid any gastrointestinal discomfort. Imagine the most midwestern small town hotdish you can, then send it to space. The Soviets allowed their cosmonauts much more spice in their food, often to the discomfort of the robust space travelers.

The first expansion of food in space was the dawn of long-term spaceflight, specifically the Soviet Salyut programs and the NASA Skylab missions. Both stations incorporated actual dining rooms for a more “normal” experience. Skylab had refrigeration available, and the Salyut stations had small gardens for fresh vegetables. This gave both crews unprecedented choice in meals and variety, an enormous morale boost.

Another morale boost came when Skylab introduced the butter cookie to NASA. Sealed in small cans with a pull tab, these cookies are still baked on site and eaten by the handful by astronauts and support people. Snacks are an important part of space travel, and it’s not shocking that butter cookies, M&Ms, tortilla wraps, and other foods are popular between meals.

The ISS does not have a refrigerator, so this is one limiting factor in what can be sent up. No fridge, no problem! The shuttle was also limited in what crews could eat. With launch delays that could stretch for days and a limited ability to replace food with a potential to spoil food for the crew could be a bit of a challenge. Commercial development of shelf stable pastries and tortillas all made it easier to supply the crew with food they wanted. Most drinks are powders that rehydrate with water and are sipped from pouches with a built-in straw.

One of the limiting factors in food choice was on board the ‘90s Shuttle-Mir missions where an American astronaut helped crew the ex-Soviet Mir space station. The first American astronaut aboard, Norm Thaagard, was told to only eat the measured and packaged food, all Russian. Most of what was supposedly available to him was unappetizing at best, and Thaagard lost nearly 20 pounds during his stint on the station. He followed orders even when his Russian crewmates introduced him to the “supplementary food,” aka the fun stuff like pretzels and chocolate. This is one reason why astronaut food choice is considered so important by NASA; give the crew what they want to maintain performance and morale.

On the ISS foods are either shelf-stable, rehydrated or packaged in MRE style retort pouches. Some organically grown vegetables are available from experiments, notably jalapeno peppers that gave a kick to taco night in 2021. The Italian space agency also sent up the station’s first espresso machine. Different nation-states have sent up cultural foods; for instance, the Republic of Korea spent nearly a million US dollars developing a kimchi recipe suitable for the ISS, while the Japanese sent ramen and Sweden sent moose jerky.

And what do astronauts drink alongside their food in space? What about alcohol? Rumors circulate that the Russians have vodka and cognac on board. Wine was considered for Skylab but ultimately never made the cut due to issues of taste. Sherry, a fortified wine, would have made the best wine in space, but due to what was perceived as negative publicity the whole operation was scrapped by NASA. Coke and Pepsi both competed for the first cola to be on board the shuttle. However, the astronauts did not like either because without refrigeration both tasted like warm, flat soda. Of course, Joe Irwin’s sample menu for Skylab shows that there was Coke in space. Remember, Skylab had refrigeration, but the shuttle (and ISS) did not. Most drinks on the shuttle and the ISS are powdered mixes added to water. It’s easier than carbonated drinks, and the physical effect is known.

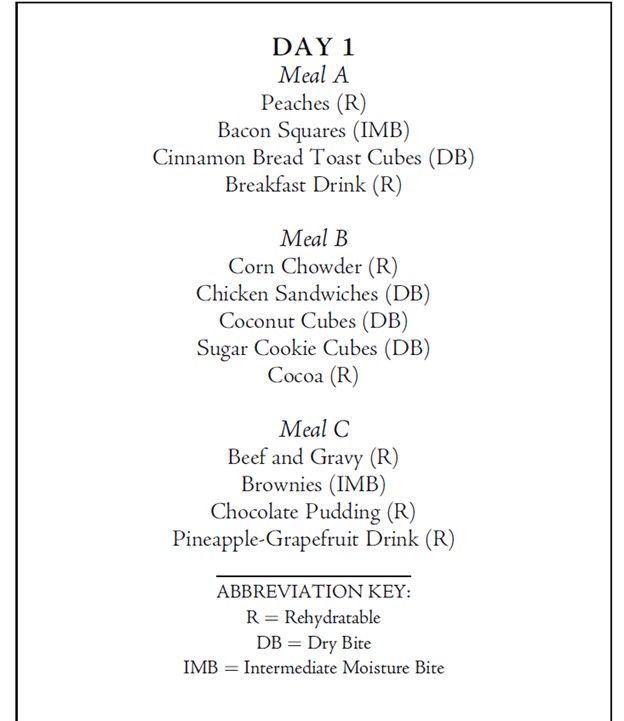

The development of military rations and space food often runs close to each other. Both are in continual development and often MRE components are used aboard the ISS. Both need to provide hardworking people with palatable calorie-laden food with at least an eye towards taste and texture. With 3D printer technology perhaps the days of ordering a full pot roast dinner on board is closer than we think. In the near future, NASA is looking at self-sustaining gardens that result in a largely vegetarian diet outside of retort pouches. A sample menu using mostly self-sustaining foods could look like this:

No matter how good or sustainable the food is, one issue with long-term spaceflight is menu fatigue. Ask a GI in 1944 who lived on K-rations for weeks and you’ll soon learn that a repeat of ham and eggs three times a week out of a can is both demoralizing and boring. NASA has developed a system to fight menu fatigue by having the astronauts themselves select what they will eat in space. We have, as Americans at least, benefited from the development, introduction, and enhancement of food in space.

Sources

- Charles T. Bourland and Gregory Vogt, The Astronaut’s Cookbook: Tales, Recipes and More

- Shane Johnson, Mr. Scott’s Guide to the Enterprise

- Bryan Burrough, Dragonfly: NASA and the Crisis Aboard Mir

- Richard Foss, Food in the Air and Space: The Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies (Food on the Go)