By Christy Tidwell

Last week, Matt Whitehead and I gave a presentation about the relationship between poetry and science for National Poetry Month as part of the STEAM Cafe series at Hay Camp Brewing. If you were not able to attend, this is a brief version of what we presented.

As members of the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences department, Matt and I (as Art and English faculty, respectively) spend a lot of time thinking about how to get students thinking creatively and engaging in creative projects. Given our work with the Science, Technology, & Society degree, we also work with connections between humanities/arts and science/technology, and we encourage our students to see creativity as something that they don’t do only in our classes but that is a part of their scientific and engineering work, too.

Our core question grows out of this work: What does poetry have to do with science?

The two might seem fundamentally dissimilar, belonging to different realms, but both offer opportunities to look carefully, communicate observations, make connections, and understand the world more fully – piece by piece, experience by experience.

Before getting too far, a note on poetry itself. When I teach poetry in my classes, I find that students are nervous about it, unsure of their ability to make sense of it. It seems – to many people – unapproachable. And to be fair, some poetry is dense and requires effort to understand. But there’s also plenty of poetry that is not challenging, that is approachable, even inviting. As an example, consider former US poet laureate Billy Collins’ “Introduction to Poetry.” Collins describes ways that he invites students of poetry to experience the work: “hold it up to the light / like a color slide,” “walk inside the poem’s room / and feel the walls for a light switch,” or “waterski / across the surface.” Instead, however,

…all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

As Collins illustrates here, poetry is something to experience, not something to solve. It is open to everyone, not only to authorities or experts.

Similarly, science – although a set of professional fields populated by experts – is at its heart also a way of thinking that is open to everyone, not only authorities. Each of us can think poetically about the world; each of us can also think scientifically about the world.

Sometimes, we can do both at the same time, and one way that poetry and science come together is through poems about science. For instance, Gregory C. Johnson has written climate change haiku to translate a climate change report into poetic language. This process uses the clear structure of the haiku to constrain the poems and narrow their focus to key details. With its 5-7-5 syllabic structure over three lines, haiku can only fit so much, after all. The form also often focuses on the natural world, and so turning scientific climate change data into a haiku is a way of emphasizing the role of observation in both science and poetry. (I’ve written more about these haiku and other climate change-related poetry previously.)

Albert Goldbarth’s poem “The Sciences Sing a Lullabye” connects science and poetry in yet another way: by personifying various scientific disciplines, making them more human and accessible. The poem’s articulations of science in this way both highlight differences between scientific fields and also emphasize the ways these sciences use narrative and relate to embodied experience (such as relaxing and going to sleep).

Robert Kelly’s poem “Science” expresses the relationship most bluntly, however, with these ending lines:

science is the same as poetry

only it uses the wrong words.

Obviously, most of us would say that science and poetry are not identical and there are meaningful differences between them, but Kelly’s statement pushes us to ask: What are those differences? And how large are they, really?

As a way to explore their similarity further, consider the steps of the scientific method:

- Observe something about the world

- Ask questions / do research

- Form a hypothesis

- Test with experiments

- Analyze the data

- Report conclusions

This structure forms the basis of how we think scientifically in modern, Western culture, and it can be boiled down to some simple activities that are not actually that dissimilar from a creative, poetic process. There’s no formalized poetic method in quite this way, but consider this list as a poetic analogue to the scientific method:

- Observe something about the world

- Ask questions / do research

- Draw connections / brainstorm

- Draft

- Critique and revise

- Share the work

Some of the concrete details are different – for instance, scientists might research by reading others’ previously published articles and poets might research by reading poetry; scientists might analyze more quantitative data where poets revise qualitative elements – but the process is very similar.

Both science and poetry are, at their core, explorations of the world and methods for understanding the world and sharing that understanding with others. Acknowledging this similarity means also acknowledging the role of creativity in the sciences and therefore taking seriously the process of generating new ideas and processes. Our Science, Technology, and Society program frequently examines these intersections (especially in our new Creativity & Collaboration in STEM minor – more details coming soon!), as does the Art + Engineering program at South Dakota Mines, which emphasizes creative, hands-on work as a way to spur innovation. Poetry is rather more abstract than this, but it does ask creators to pay close attention to what surrounds them, to think about details, and to put things (in this case, words and images) together in new ways. Valuing both science and poetry – rather than separating them – gives us more ways to understand the world.

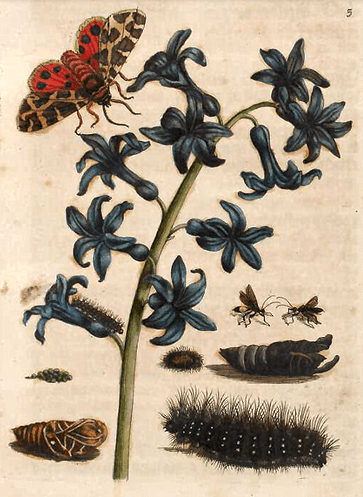

The bulk of our time at STEAM Cafe was spent actually creating poetry. We brought pages from historical scientific texts by Charles Darwin, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Georges Cuvier, and Humphry Davy for audience members to use to create blackout poetry, and we chose these historical texts in part as an acknowledgment that science has not always been so separate from humanities and arts. Erasmus Darwin – grandfather of Charles Darwin – was a naturalist, a physician, and a well-known poet; Humphry Davy, a chemist, wrote poetry about his scientific work; and many scientists and naturalists of earlier periods were accomplished visual artists. Maria Sibylla Merian (see image) was an accomplished entomologist as well as a botanical illustrator. Charles Darwin’s illustrations of finches are also well-known as an illustration of his scientific thinking about evolution.

Merian, Darwin, and others who illustrated their work did so not solely out of a love for the arts but as a pragmatic necessity. Photography did not yet exist, so naturalists needed to be able to record their observations accurately as they traveled the world. Their creations, however, go beyond mere accuracy to beauty.

Scientists writing poetry about their scientific work are even more interesting, because there was no logistical need for it. They could write down their observations in more mundane styles, without the poetry. But so many of them did write poetry, as scholars Daniel Brown and Gregory Tate point out, that it seems to reflect a deeper connection. Brown writes that poetry’s formal elements, specifically “the unruly play of the pun, the tense relation of analogy, and the variegated repetition of rhyme” was, similar to their scientific work, “a model of lively knowledge” (261). And Tate argues that writing poetry allowed scientists “to carry on their scientific investigations by other means, providing them with a form of expression in which they could document their empirical study of nature and also speculate on its broader philosophical significance.” It was, in other words, another way of doing science but also a way of adding to that scientific work, connecting it to the bigger picture, humanistic questions it raised.

This history is vital to remember because – without it – we too easily forget how closely connected science and the arts and humanities are. Recent attitudes about science might make it seem like it’s “natural” for science and the arts to be distinct, but historical cases like these remind us that this is not the case. In fact, it might be more “natural” – or perhaps more human – to connect them, to see both scientific learning and the arts/humanities as ways of understanding the world from a human perspective.

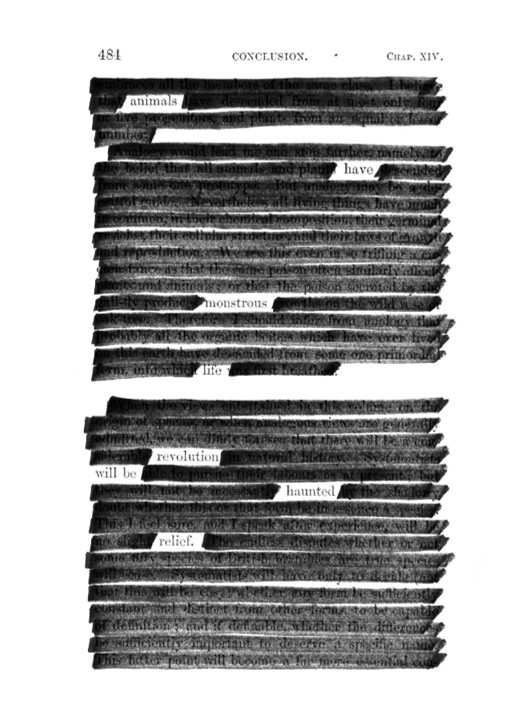

To conclude, if you would like to make your own science-based blackout poetry, all you need is a page of scientific text and a marker. Choose a page, like one of these (from Charles Darwin and Georges Cuvier) and follow the instructions below.

Blackout poetry instructions:

- Skim the page you’ve chosen and see what words grab your attention. Circle or underline the ones you like.

- See if any of the words you’ve marked seem to work well together – if narratives, images, or themes arise.

- Use a marker to black out everything but the words you want to keep.

- Read your poem and decide if you want to make changes or decorate the page.

- Give your poem a title.

Completed blackout poems can look a variety of ways, but here is one example, made using the above page from Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species: